Behind the tears, Brock Stassi has an inspiring story to tell

MLB columnist

CINCINNATI – Don’t listen to the movies. There is crying in baseball.

Spend a life on the precipice of good enough, in the shadow of flesh and blood, wedged in the back of a bus that leaves in darkness and arrives in light, forever loving it when it never seems to love back, and the game will forgive a quivering lip and eyes so welled with liquid the levees break. Forgive, actually, isn’t even the right word. Appreciate.

Because baseball players are reared to be automatons, jejune and emotionless and embodiments of this ideal that evolved through the years not like a virus infecting it so much as a necessary defense mechanism against the inevitability of constant failure. Baseball tests, and it prods, and it judges, and it hurts, and all who play it plumb the depth of their resolve, and deep down, somewhere behind the façade they must create, every one of them wants to have a good, full-body, exhaust-the-vapors heave like Brock Stassi.

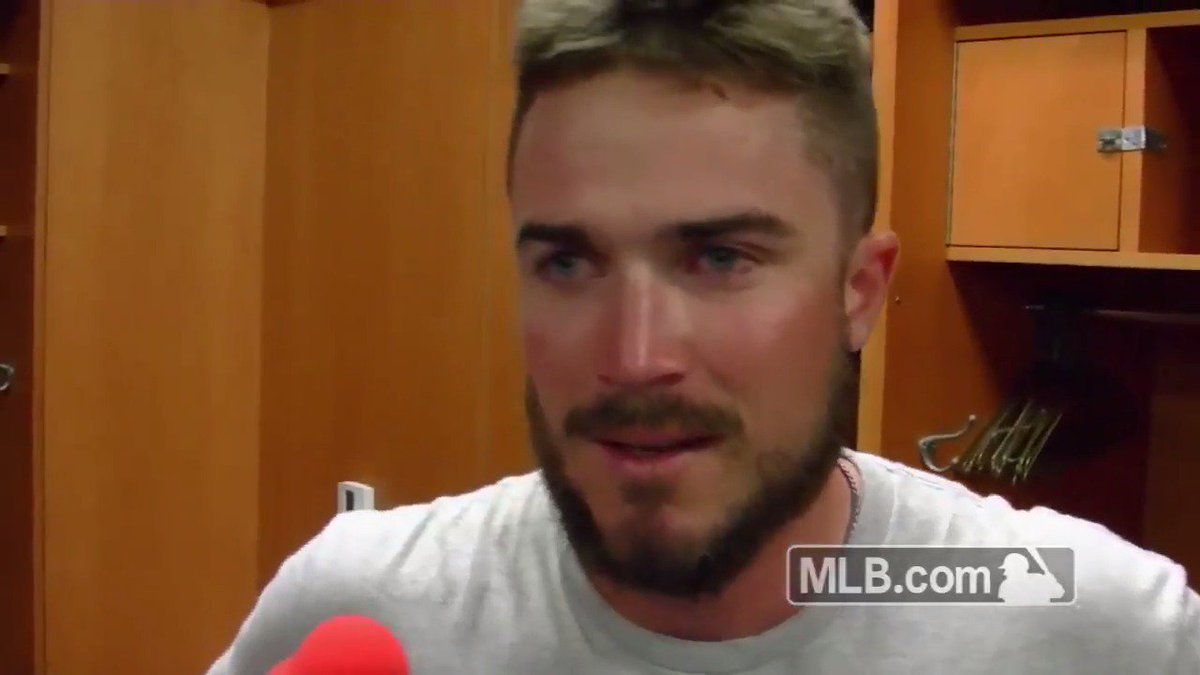

Nothing in baseball this spring resonated quite like a 27-year-old career minor league first baseman attempting to speak without being interrupted by his inability to do so. Failure had grown into success, disappointment into joy, a minor league existence into a major league job with the Philadelphia Phillies, and much as Stassi tried to put his life into words, in that moment nothing told his story better than tears.

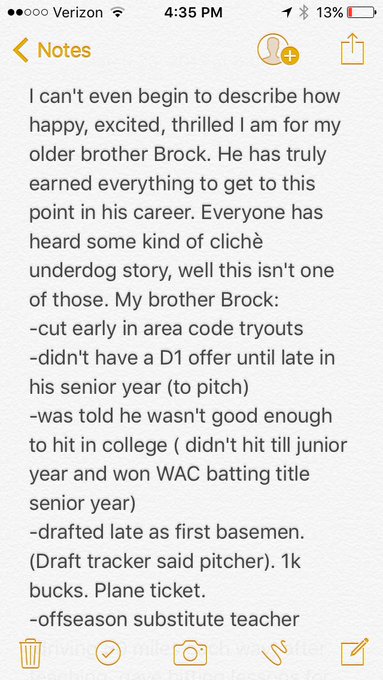

There is a deeper story there, though, deeper than the surface details of the 33rd-round draft pick who signed for $1,000, a plane ticket and a roster spot, who substitute taught in the offseason because no winter-ball team wanted a soft-sticked first baseman, whose viral moment earned him fans and admirers and did the impossible: made Philly go soft.

“I didn’t mean to cry like a baby on camera,” Stassi said. “Everything I’ve been through hit me at once.”

.@Phillies rookie Brock Stassi just made his first #OpeningDay roster.

His reaction? Amazing. http://atmlb.com/2oh3xOZ

Even the hardest can be suckers for something so visceral and relatable. In the moment, with cell phone cameras trained on him and his mind in need of more RAM to process everything going on and questions about how he felt, Stassi thought of everyone but himself. His mom and dad, neither of whom answered the phone when he called with the news because they were at work. His wife, who’d seen the dregs of minor league life and never wavered. And Max, his best friend and rival, his foil and companion, his little brother who made it big first. The tears were for them.

Now opening day was here, Philadelphia Phillies vs. Cincinnati Reds. Opening day is a million metaphors, a rite of spring that serves as a reminder that baseball, for its many foibles and flaws, still matters deeply. It means something different to everyone, and for Brock Stassi, this year’s was about redemption and validation and, more than anything, family.

***

Over the last 141 years, 18,593 men have played Major League Baseball. Tens of thousands more have stalled in outposts across the maps, country towns and medium-sized cities, one step or two or three or too many to bother tabulating from the big leagues.

Brock Stassi comes from a family full of baseball players. (AP Images)

Brock Stassi played in Williamsport and Clearwater and Lakewood and Reading and Lehigh Valley, beholden to the idea that someday he might actually fulfill what he promised himself all those years earlier. The life was his inheritance. His grandfather, Bob Stassi, a catcher of moderate talent, stalled out after stints in Albuquerque and Hollywood. His father, Jim, played in Fresno and Shreveport and Phoenix and walked the same path as Bob in position and result. Jim and his wife, Racquelle, had three sons. The youngest, Jake, played college ball. The eldest, Brock, was the vagabond. Max Stassi was the 18,111th player in major league history.

Every day, the boys’ grandfather would pick them up from school and ask whether they wanted to go to practice with Jim, the coach at Yuba City (Calif.) High, or head home. Brock and Jake chose “Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball” on Super Nintendo over the real thing. Max went to the field.

“If you’re the older brother, you’re supposed to be better than your sibling and get more recognition,” Jim said. “That didn’t happen. Ever since he was a little kid, Max would come to the weight room with me at 5:30 in the morning to work out, and his brother was still home sleeping. That’s fine. That’s what he chose to do.”

It’s not that Stassi lacked Max’s preternatural talent. He pitched with both arms until he was 10, when Jim urged him to stop throwing right-handed. The left-handed-throwing and -hitting version of Stassi was plenty good, even as he treated the weight room with disdain and loved snowboarding as much as baseball. He just wasn’t Max.

Junior year of high school rolled around, and as recruiting letters poured in to his friends’ homes, Stassi heard from one school. UC Davis called to say it wanted him to come on an official visit. Stassi never heard from them again. By the end of the year, as he stared at a future with no baseball prospects, Max, only a freshman, committed to UCLA, annually one of the country’s best programs.

The fall before Stassi’s senior season, Scott Golby, a longtime family friend and scouting supervisor for the Marlins, met with Stassi at his school and presented him with a choice: He could go to junior college and play ball and snowboard, or he could teach himself to work hard and convince a bigger program he belonged. Stassi took the challenge, earned three offers and committed to the University of Nevada, where his father had played, because the coach said he would allow Stassi to pitch and hit.

The other programs viewed Stassi strictly as a pitcher. Even if he could hit, who cares? He was left-handed and threw strikes. That trait plus that skill means a future in pitching.

“Very few people believed in him,” Max said. “The thing that I can say is true is he truly never doubted himself. Throughout the offseason, he would even tell me, ‘I’m gonna be on that flight to Cincy. Watch.’ ”

***

In the fall of his sophomore year, Brock Stassi kept pestering Gary Powers to let him hit. Powers had been the coach at Nevada for two decades, and while he knew Stassi could hit a little, he needed a left-handed arm more than anything. Still, this was fall ball, and Pat Flury, a Reno native who had peaked pitching in Triple-A and spent a year playing in Japan, was attempting a comeback and wanted to face some live hitting.

“It’s the end of practice,” said Joe Wallace, Stassi’s teammate and roommate at Nevada. “We’d already scrimmaged. And they were like, ‘We’ll let Brock hit.’ He goes triple, bomb, double, single in four ABs. That was it. And the rest is history.”

By spring, Stassi was in the lineup regularly in addition to his pitching duties. The responsibility of both meant no more of his Thursday night freshman ritual when he and Wallace would chase mediocre dorm-cafeteria pizza with two 40-ounce bottles of Mickey’s Fine Malt Liquor. Stassi had learned in high school how to work hard. Now he needed to learn how to work smart.

“He doesn’t have a whole lot of speed,” Powers said. “And he wasn’t the biggest and strongest kid coming out of high school. But he knew how to use his tools to be successful at playing the game. He understands that there’s more than just one way to do things. You don’t have to be a big, strong, powerful guy. You just have to be yourself.”

Himself was good enough to merit an invitation to the Cape Cod League over the summer. He landed in Boston on the second day of Major League Baseball’s draft, when the Oakland A’s chose Max and gave him $1.5 million, a record bonus for the fourth round. As his little brother started on his ascent to the big leagues, Stassi couldn’t even convince his manager that summer, Kelly Nicholson, to let him hit.

He returned for his junior year at Nevada, won WAC pitcher of the year honors and hit .364. Barely anyone noticed. On draft day in 2010, a St. Louis Cardinals scout told him to have his phone ready. It never rang. He got a call on the third day, from the Cleveland Indians. They chose him in the 44th round. He asked if they could send a scout to watch him hit in the Northwoods League, where he was playing summer ball. Cleveland wanted Stassi to pitch. He didn’t sign.

Brock Stassi hit six homers in spring training to help make the Phillies. (Getty Images)

There’s a truism in baseball, that the game is the great arbiter, that it will be more honest with you than you ever can be with yourself. That’s what left Stassi so confused. He didn’t lack self-awareness. He knew his limitations. His future was in the batter’s box, not 60 feet, 6 inches from it.

Stassi hit .360 as a senior, graduated and waited for draft day. Around the 10th round, a Phillies scout named Joey Davis reached out to him and told him to stay by his phone. He’d heard this before. Stassi went to the golf course with his father, and, standing on the 18th fairway, it rang. Davis apologized. He was trying to convince his bosses to take Stassi. They weren’t biting. He went to bed that night livid.

“I’m thinking it might not happen, that my career is done,” Stassi said. “I’m devastated.”

The next day, as he slept, Stassi’s door burst open.

“Dude,” Max said. “You just got drafted by Philadelphia.”

Stassi went with the last pick of the 33rd round in the 2011 draft, 1,021st overall. Originally, on MLB.com’s draft tracker, he was listed as “LHP.” By the end of the day, the position had changed to “OF.”

The Phillies gave him $1,000 to sign. On the night his bonus came through, Stassi lost 30 percent of it playing blackjack at Mohegan Sun. He didn’t mind. He was a full-time hitter, and that’s all he wanted.

Stassi just worried he was blowing the opportunity. He hit .200 in short-season Class A ball. Twenty-two-year-olds who can’t hack it in the New York-Penn League don’t often endure the onerous bus trips of higher levels. The Phillies saw something in Stassi anyway. His makeup was off the charts. When they sent him to extended spring training in 2012, he didn’t sulk. During a session with Dr. Jack Curtis, the organization’s psychologist, Stassi had learned to appreciate what he did have. Something as simple as a bed to sleep in, a hot meal, a perfect day when the sun gleams off the ballpark’s grass. In clubhouses full of fear and nerves and testosterone, he was a calming presence.

His other saving grace: “He had Keith Hernandez hands,” said Mickey Morandini, a minor league manager of Stassi’s who is now the Phillies’ first-base coach. Hernandez is widely regarded as the best defensive first baseman of all-time, and any comparison to him is the highest compliment. In the minor leagues, where errors can wreck an infielder’s psyche, Stassi’s habit of preventing them won him fans inside the organization.

Brock Stassi’s saving grace during his career was his glove. (AP Images)

The rest of the baseball world didn’t have much time for him. While other players went to winter ball, teams weren’t much interested in a 25-year-old first baseman who never had slugged .400. Stassi filled his offseasons instead with side jobs.

“When I was going to workouts for the upcoming season,” Max said, “he was putting on his collared shirt and slacks to go substitute teach, then give hitting lessons after.”

Even as Stassi seemed to plateau at Double-A, the Phillies brought him back in 2015. And that spring, they noticed a change. This was not the Brock Stassi of past years, with a swing that on its best days sprayed line drives and its worst killed more fescue than a tub of Roundup. This was something different altogether.

“A lot of people think at 25, you are what you are,” Morandini said. “He wasn’t.”

***

Late at night before the 2015 season, at the apartment he shared with Stassi, Max would stand in the living room and start swinging a baseball bat. He was the rat of the Stassi pack, and that translated into his professional life, when he immersed himself in the world of hitting mechanics. For the previous two years, Max had cups of coffee with the Houston Astros, who had acquired him in a trade from Oakland. He wanted more.

He knew Josh Donaldson, who would win the American League MVP that eason, through their time together in the A’s organization. Donaldson transformed his career with the help of a hitting guru named Bobby Tewksbary, a former indy ball player who studied history’s best hitters and realized almost every one elevated the ball with their swing. He helped retool Donaldson’s swing and since then had been a maharishi for struggling hitters, including Max.

All those midnight swings from his brother got to Stassi. He wanted to know what his bat path said about him. Max took video and sent it to Tewksbary, who understood why Stassi managed only 18 home runs in his four professional seasons. He embodied so many of the clichés Tewksbary believed robbed hitters of power. Stassi stayed tight and had a short swing and got on top of the ball. These tropes, Tewksbary believed, were rubbish.

So he sent the video back to Stassi with some voiceover commentary. He wanted Stassi to adopt a significant leg lift. He wanted him to lift his hands slightly – a hitch, in the parlance of some, but one that Ted Williams and Barry Bonds and Albert Pujols and Miguel Cabrera all employ – that would allow Stassi to get his bat behind the ball earlier. And if he did both of these things, Tewksbary believed the plane of Stassi’s swing would change from chopping at the ball to lifting it.

“You’re giving yourself more time to make a decision,” Tewksbary said. “You’re building what most people view as a long swing, but you’re able to start your swing without committing. You create a scenario where you get the best of all worlds. It’s like a perfect storm of swing mechanics.

Max Stassi made the majors with Houston in 2013. (Getty Images)

“When guys start to buy into this stuff, there’s risk. These are professional baseball players who are very good at what they do, but if this doesn’t work, they may get released and have to get a normal job, and that sucks. I try to be respectful that they’re trying something that can be dangerous and scary and nerve-racking.”

Lucky for him, vulnerability works with Stassi. Challenges made him better in high school and college. This was no different. It was still baseball. It was still staring at a pitcher and guessing what he’s going to throw even though there are infinite permutations – up and down and right and left and fast and slow and straight and bent in finite space, yes, but one where even a fraction of an inch makes the difference between a weak groundout and a home run – and doing all that in less than four-tenths of a second.

Thing is, it worked. For the first time as a pro, Stassi hit .300. He hit 15 home runs and drove in 90 runs. He walked 77 times and struck out just 63. He won the Eastern League MVP award. He rewarded the Phillies’ faith and saved his career. And while another solid season at Triple-A last year and a dominant winter-ball turn in Venezuela didn’t convince the Phillies to add him to their major league roster – 29 teams passed on getting him essentially for free in December’s Rule 5 draft – it did give him a place in their major league camp this spring.

Stassi made sure the team noticed him. Hitting coach Matt Stairs grew fond of yelping “Engage!” every time Stassi loaded his hands. Morandini beamed that his conviction that the bat could catch up to the makeup and glove had proven true. And the team’s executives marveled at what they’d happened upon: a 33rd-round pick signed for a thousand bucks who hammered six home runs in spring training.

Before the tears, Brock Stassi was the Phillies’ little secret, and they liked it that way. He never would be Ryan Howard. He may never be much more than a bench bat. But he would be something that next to nobody ever would have predicted.

***

On the first day of spring training this year, Brock Stassi spoke with his father.

“Dad,” he said, “I’m going to make this team.”

“Why not you?” Jim said.

The Phillies kept asking themselves the same question. Why not him? Because he was 27 years old, and 27-year-old rookies simply don’t crack opening day rosters? Because the Phillies, in the midst of a rebuild, might be better off breaking camp instead with a 13th pitcher or a veteran with major league experience? The more they wondered, the more they concluded Stassi was their best option.

“We started spring training with 62 names and actually added one, so 63,” Phillies general manager Matt Klentak said. “And the vast majority of those, you have to sit down and tell them they’re not going to make the major league team. It really does make the few at the end where you get to tell the guy he’s going to open the season with the major league club all the more special.”

On Thursday, Stassi was called into the office of Phillies manager Pete Mackanin. Klentak was there, along with assistant GM Scott Proefrock, scouting director Joe Jordan and bench coach Larry Bowa. Mackanin told Stassi he needed to do only one more thing: Pick a number, because he was going to Cincinnati. A huge grin broke across Stassi’s face. He couldn’t stop thanking the group for the opportunity.

“Kind of exactly what you would expect from Brock Stassi.” Klentak said. “It’s incredible the way it has worked out so far. And this is far from the end of his story.”

Its next chapter came Monday. Stassi slipped on his gray pants with a red stripe down each leg, then pulled on his jersey. He stretched with the other 24 Phillies, took batting practice in the last group, retreated to the clubhouse and spent the first eight innings in the dugout, until the pitcher’s spot in the batting order came up and he stepped into the on-deck circle. At 6:42 p.m., a voice boomed across the P.A. system: “Now batting for Philadelphia, No. 41, Brock Stassi.”

In Section 116 down the third-base line, rows DD and EE were filled with nearly 20 people who had flown across the country for this moment. Jim and Racquelle. Jake and Joe. Stassi’s wife, Jana, who was his high school sweetheart, and Gabe Foster, a longtime family friend who married the two in December and thinks so much of Stassi he named his 3-year-old son Brock. Stassi’s grandparents and in-laws and aunts and uncles.

The only person not there was Max. He watched from Fresno, his father’s old stomping grounds, where he’ll begin the season with Houston’s Triple-A affiliate.

Stassi dug in against Reds reliever Michael Lorenzen. He put almost all of his weight on his back heel, a trick he learned last year when, amid a slump, he watched video of Donaldson breaking down his swing.

Lorenzen threw a cutter that sizzled in just below the knees at 95 mph. Stassi stared at it.

Jake took a picture of the scoreboard. Jana craned her neck for a better view of the plate. Jim and Racquelle sat statue still.

The next pitch was another cutter, this one 94 mph. It was low, too.

“Two-oh,” Wallace said. “Get yours.”

Lorenzen went to his fastball, a 97-mph pea just low of the zone. Stassi didn’t bite.

“Give him the green light,” Wallace said. “Three-oh tank, right here.”

He was joking, but as Stassi looked at third-base coach Juan Samuel for the sign, there it was: an invitation for the 27-year-old rookie in his first major league at bat to hack away 3-0.

He didn’t. That’s not Stassi’s style. Lorenzen pumped in a 98-mph fastball for a strike.

Brock Stassi's first MLB PA

Phillies' Brock Stassi makes his first major league plate appearance on Opening Day 2017 against the Reds

Stassi’s heartbeat picked up. It was still a hitter’s count. He lifted his bat, readied himself to flatten it and cause damage.

Cutter at 94. Low once more.

“Attaboy!” Joe said.

“We’ll take that AB!” Foster said. “We’ll take that AB right there!”

chris jones¯\_(ツ)_/¯ @LONG_DRIVE

Brock Stassi draws a walk in his first MLB at bat while his fam watches

Officially, it was not an at-bat. That will come soon enough, maybe this week, maybe next. This was plenty. Stassi was standing on first base, owner of a career 1.000 on-base percentage and a title far, far more important.

“He’s a big leaguer,” Jim said. “He’s a big leaguer.”

***

Earlier this week, before he decamped to Fresno, Max Stassi made a stop in Yuba City to visit his family. Even though publicly he gave the video of his brother’s waterworks greater context with a tweet talking about so much of what he’d endured, Max wasn’t above accusing his brother of shedding crocodile tears.

Congrats to my big brother @brockstassi28 !!! I couldn't be happier!!!!!

“He knew what he was doing!” Max said.

He was kidding, of course, the remnants of their childhood love-hate relationship cropping up every now and again. Just as Stassi was angrier than Max that he slipped to the fourth round of the draft, Max’s excitement Thursday may have exceeded Stassi’s. Max knew. He knew what it takes to make the major leagues. He knew the work, the sacrifice, the mental anguish, the physical toll. He knew, even if he’d never admit it, that his brother would not be a big leaguer without him.

He was one, though, and the world was loving him for it. Congratulations from strangers nuked his Twitter mentions. Mike Schmidt texted him congratulations. Vince Papale, the original Philadelphia folk hero, passed along a message through the Phillies’ P.R. department: “Tell Brock he’s invincible. I want his movie rights.”

After the Phillies locked up a 4-3 victory, Stassi walked toward the stands down the third-base line and greeted his family. He and Jana kissed. He posed for pictures with everyone. His grandmother vowed to frame theirs. Fans hung around as well, asking for autographs and snapping photos and appreciating the accessibility of a real major leaguer.

Stassi is enjoying the fringe benefits. He estimated he ate eight plates’ worth of sushi on the charter from Florida to Ohio. He introduced Stairs and others to one of his secret weapons: a 60-ounce bat that helps hone his swing. Not only had he done it, he had done it his way.

And that promise to himself, the one from his childhood? He’d kept it.

“I remember being a kid and going to AT&T Park in San Francisco when I was 10 or 11,” Stassi said. “That’s when I first started to get a feel for things. Standing down the right-field line during BP, I’d look around and think, ‘Man, all the people in this stadium probably had aspirations to be a big leaguer.’ I really, really believed, even back then, that one day I’d be on one of those fields. I don’t know why that moment really stuck with me my whole life. Everybody was watching these guys. I could be the one of these 40,000 people that steps on the field one day.

“And I did.”

MLB

MLB

chris jones¯\_(ツ)_/¯ @LONG_DRIVE

chris jones¯\_(ツ)_/¯ @LONG_DRIVE

Max Stassi

Max Stassi