Sale is one of just six pitchers in MLB history to stand 6’6″ or taller and weigh 180 pounds or less.

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine’s July 22 Body Issue.

“Pitcher’s got a rubber body…”

CHRIS SALE PULLS down his black cap, shading his cropped beard, and breathes deeply. He had looked relaxed earlier in the evening, flipping the ball between his throwing hand and glove, joking with the grounds crew and high-fiving teammates. But when Oakland’s Yoenis Cespedes walks into the batter’s box hoping to erase a slim 1-0 White Sox lead in the fourth inning at U.S. Cellular Field, all playfulness disappears. A skeleton on the mound, the 6’6″ Sale prepares to unleash choreographed chaos.

It starts with a high, sweeping leg kick, then his torso hunches forward as his bony left elbow launches into the air. His upper body morphs into an inverted W, a strained position akin to a scarecrow’s in which elbows are higher than wrists and shoulders (see previous page). As his chest opens up, he rotates, slams his front foot and flings his arm around like a slackened rubber band. Cespedes watches as a backdoor slider curves over the plate. Then he pops up the next pitch, another slider, behind home.

As Sale works, the whole production looks awkward, even painful, every throw inviting a snap of the ulna. One hundred eighty pounds of mass don’t usually twist like this — aren’t supposed to twist like this. As general manager Rick Hahn says, “There’s a fair amount of funk to Chris.” Even 6’10” Randy Johnson, who was rail thin with a violent motion, isn’t a parallel; he carried 45 more pounds than Sale. “My delivery is different,” the 24-year-old agrees. “It’s unique.” Sale wastes a two-seamer upstairs before uncorking two slicing fastballs, both 94 mph, that Cespedes barely fights off. Ahead in the count, Sale contorts again and drops a sweeping slider low over the plate. Cespedes swings so hard he is thrown off balance — and misses.

Were it not so compelling, the sight of so much force from a body that looks so frail would make you change the channel cringing. Between his bird-bone physique and the inverted W, an indicator of a future blown-out elbow, Sale is the poster child for the hurler destined to break down. “I’ve never seen somebody [at this level] with that type of delivery and arm action,” says Nick Hostetler, Sox assistant director of scouting. It takes more strength and torque for a skinny pitcher to generate the same velocity as his heftier cohorts, which is why pitchers under 200 pounds have become endangered as scouts look for stronger bodies and teams stress weight training. But truth be told, Sale would’ve been freakishly thin in any era. Since 1950, only three other pitchers — all relievers — have stood 6’6″ or taller and weighed 180 or less, and they aren’t exactly household names: Jim Pearce, Dave Pavlas and Jerry Blevins.

Yet according to Baseball Reference, only two first-round picks since 2008 — phenom Mike Trout and reigning NL MVP Buster Posey — have more wins above replacement. In 2012, Sale’s first season as a starter, he posted a 17-8 record, 192 strikeouts and 51 walks. He’s been even better this year: fifth in the majors in WHIP, 10th in adjusted ERA and fanning more than four hitters for every walk through June 28.

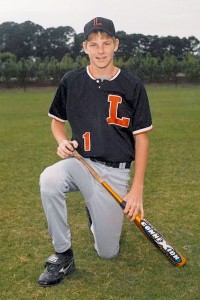

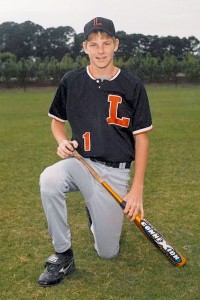

Nobody saw this coming. Though he was raised in baseball-obsessed central Florida and played catch with his dad on a mound in the backyard, Sale was no prodigy. He was a “young kid without a lot of muscle trying to catch up with his coordination,” says Mike Campbell, who was his coach at Lakeland High. Sale’s father, Allen, says, “He’s always been all elbows and knees, coming at you like the rubber man.”

Chris Sale

Courtesy of The Sale Family Sale, before he grew six inches in high school.

As the teenager got longer, he didn’t fill out. He also never lost his alarming flexibility. “Even after he got tall in high school, he could lie on his stomach, lift his feet over his back and scratch his eyebrows with his toes,” Allen says. “I’ve seen little girls in gymnastics do things like that, but when you see a kid tall enough to dunk a basketball put his feet over his head, it’s hard to watch.”

His starts were too. Sale couldn’t figure out his frame; some days he’d look dynamite, others erratic. “He’d be at 80 or 82 mph,” says Florida Gulf Coast University coach Dave Tollett, the only D1 coach to offer Sale a scholarship. Then all of a sudden, when arms and legs put it together, he flashed 88.”

Sale was lit up in 2007, his first fall at FGCU, losing three decisions and serving up a walk-off homer to a pitcher. He seriously considered quitting. Instead, he went to Wisconsin for the collegiate summer Northwoods League. With the La Crosse Loggers, he worked with pitching coach Derek Tate and special assistant coach (and former MLBer) Greg Vaughn.

Shoulder conditioning came first. “Chris’ body wasn’t in throwing shape,” Tate says. “He would pitch an inning of relief, then be so stiff he couldn’t pick up the ball for three days.” The coaches dropped his arm angle from what Tate calls a full three-quarter to a low three-quarter slot, hoping to create lateral movement on the ball. The change made his delivery look even more disorderly, but Sale gained velocity almost immediately.

Over his final two college seasons, Sale struck out 250 batters while walking just 41. By the 2010 draft, the White Sox’s Hostetler figured there was “zero percent chance” Sale would still be available by the 13th pick. But when other clubs passed on the threat of a shredded elbow, Chicago jumped — injury risks be damned. “I don’t want to say I wrote off [his mechanics],” Hostetler says. “But they became less of a concern the more I saw.” The Sox weren’t too concerned about babying Sale either. With Chicago holding a slim division lead, its lanky signee — who had faced just 43 hitters in the minors — got the call less than two months after the draft. Quick promotion is an understatement: The median minor league batters faced by the 26 All-Star pitchers in 2012 was 1,198. No other had faced fewer than 100.

Nearly three seasons later, Sale is more and more economical. So far in 2013, he’s thrown more first-pitch strikes and fewer pitches per inning, giving manager Robin Ventura a longer leash. Through 14 starts, he had been pulled before the seventh only three times, had avoided the disabled list and was on pace to surpass 2012’s 192 innings pitched.

Will this durability last? Former big leaguer Tom House, a motion analyst and guru of pitchers and QBs, isn’t convinced Sale’s wing is doomed to break down, like those of skinny aces with strange motions such as Stephen Strasburg (Tommy John surgery at age 22) and Tim Lincecum (velocity loss since 2008). “Chris gets there differently than a lot of people, but he’s perfect at release point,” House says. “His eyes are level and he’s letting the ball go eight to 12 inches outside his driving right foot.” And Sale’s uncanny pliability allows him to pick up speed without overexerting, says Rick Lademann, a Florida-based personal trainer Sale hired last winter, who calls his client a “freak.” “His internal and external rotation in his shoulder is fantastic.”

If he’s still a waif, he is, as Lindsay Lohan might insist, “not skinny for the wrong reasons.” He attacks clubhouse spreads and inhales Whataburgers and Whoppers. “He eats more than anybody on earth,” 285-pound first baseman Adam Dunn told The Wall Street Journal. “I’ll gain 10 pounds just watching him.”

Easygoing and quick to smile, Sale just laughs at his metabolism: “I hope I can start adding weight soon.” Last winter, when he did gain about 15 pounds, he somehow lost 2% body fat in the process. That’s the Sale curse. Chris’ grandfather was 6’4″, 145 during his days as a paratrooper; his jumpmaster joked that Harold Sale was the only guy ever to jump out of a plane and float up. As for Sale’s 3-year-old, Rylan? “We took him to the doctor. He was in the 80th percentile for height and 30th for weight,” Sale says. “Tall and skinny — go figure.”

Go figure is what Sox GM Hahn did in March, when he signed Sale to a five-year extension worth up to $60 million with options. It was a calculated gamble between, as Hahn saw it, locking down a front-line starter with a theoretical risk of injury and watching said starter dominate through his prime in another uniform. “For us, the choice was easy.”

As for what the franchise will do if his arm does indeed snap: That’s a question South Siders hope never has to be answered.